My grandmother, Annunziata Papa was the glue that bonded our family together. Even though my grandfather was the head of the house, it was my grandmother’s voice that everyone listened to as the final decision. She emigrated from Italy shortly after my grandfather and they were soon married on October 31, 1920. They settled in Central New Jersey and lived in an Italian immigrant community. Like most Italian grandmothers, she was an exceptional cook and earned money by taking in sewing. Her role was to take care of the household, her husband and eight children. She was always surrounded by her family and there was an abundance of love that continuously radiated from her. Grandmom instilled in us strong family values and traditions that have been passed down for generations. I was only nine when she passed, though some memories have faded, the most vivid are the ones of her sitting down at the kitchen table teaching me how to draw chickens and roosters on scratch pieces of paper.

This assemblage is inspired by the notions of sewing and mending. Countless threads represent the interweaving of traditions, values and teachings cocooning my grandmother’s portrait symbolizing the core strength, devotion, resilience, and an unbounding love of family.

My maternal grandfather was the patriarch of our family. He was a shoemaker who owned his own shop. I have fond memories as a child of visiting him at his store in Bound Brook, NJ. The smell of leather as he tapped and stitched with the sunlight streaming through the small front windows, highlighted by the smoke from my grandfather’s cigarette holder. At the end of the visit, my grandfather would always open his work drawer and hand me black licorice candy. The scent and flavor of black licorice is a powerful sensory memory trigger and to this day I love anything flavored with licorice or anise. It’s a comforting feeling that reminds me of my grandfather, Alfredo Papa.

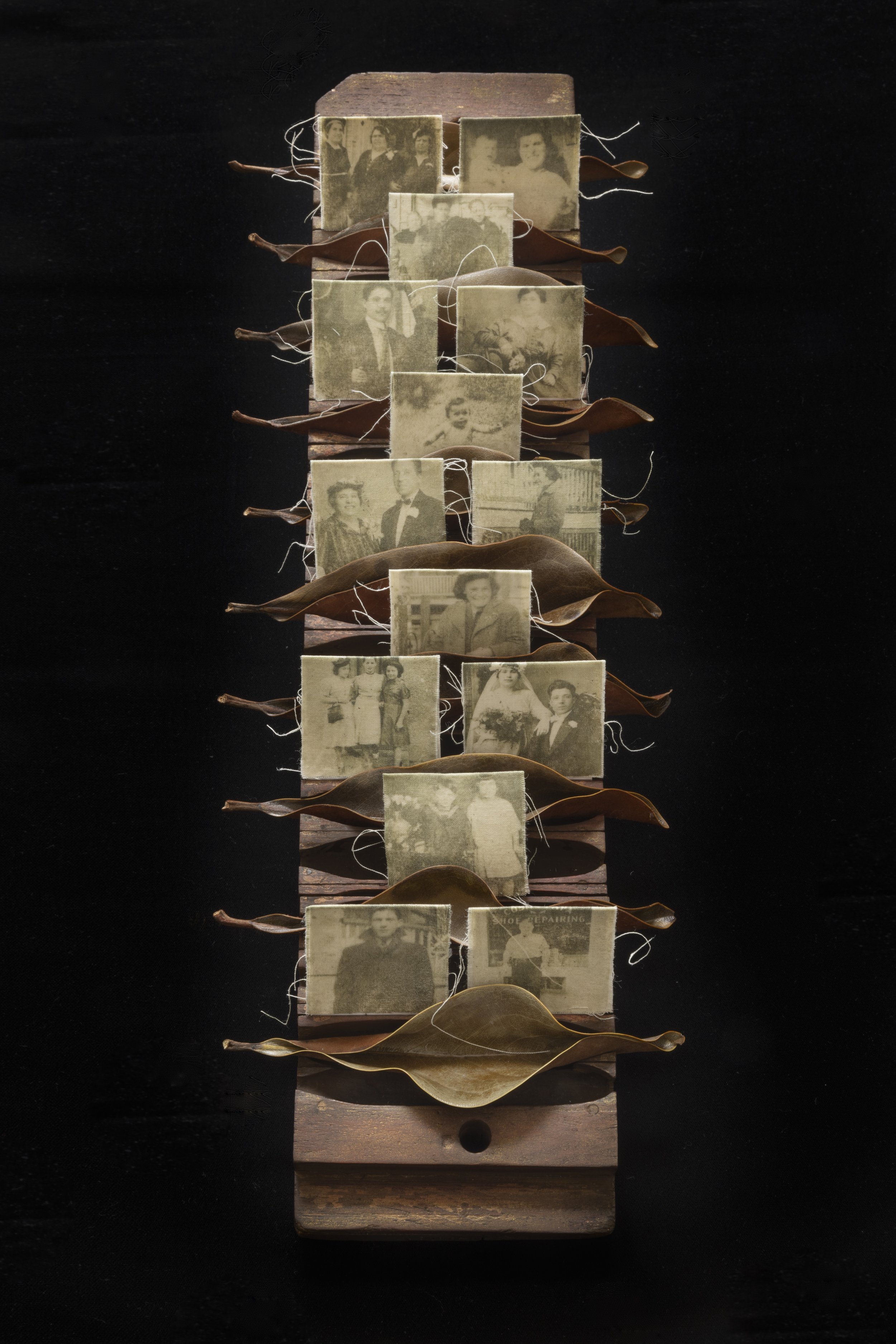

Inspired by the eyelets, hooks and laces of my grandfather’s shop, Alfredo uses the foundation of memory and looks at our relationship with the family archive and how it serves as a memorial function.

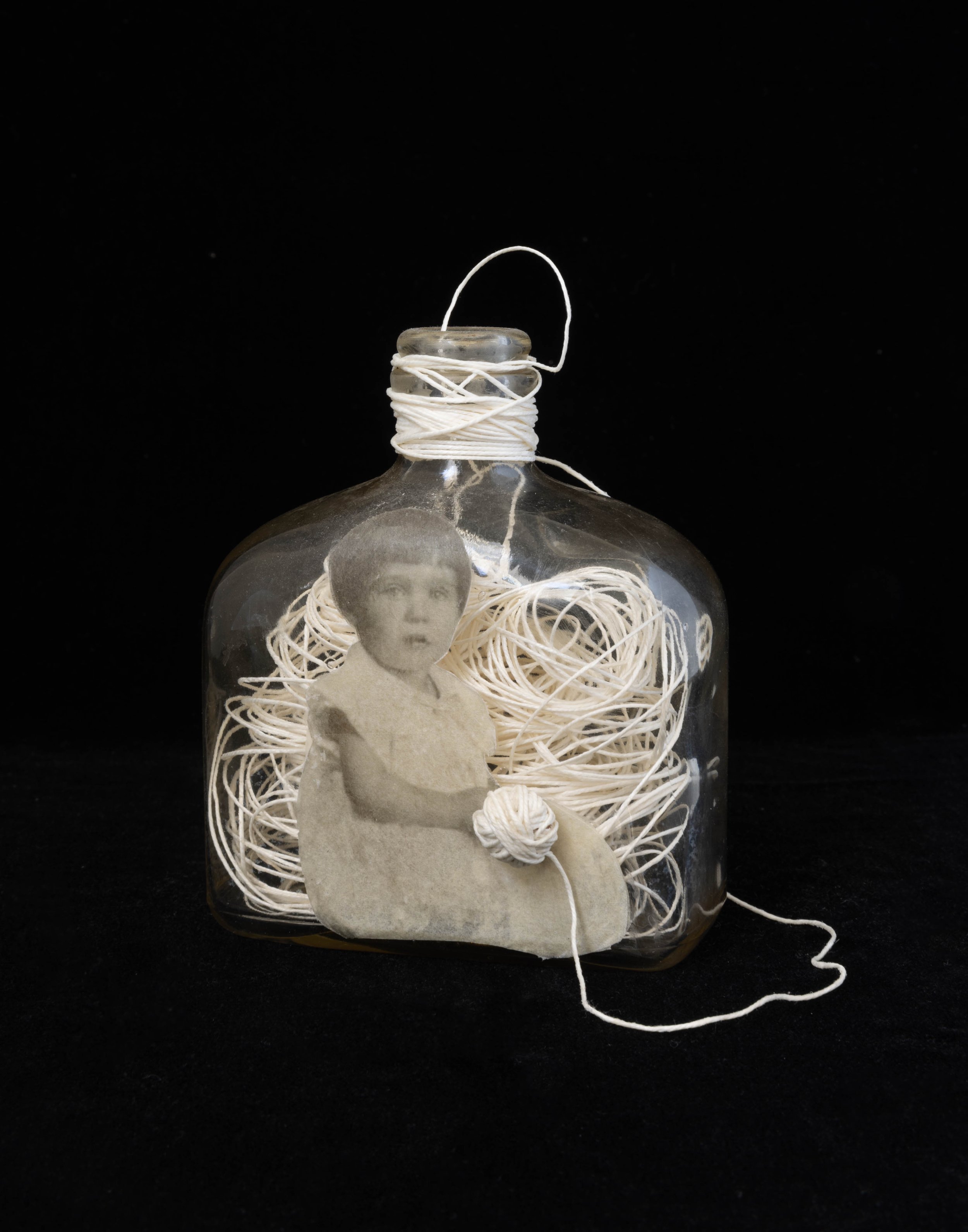

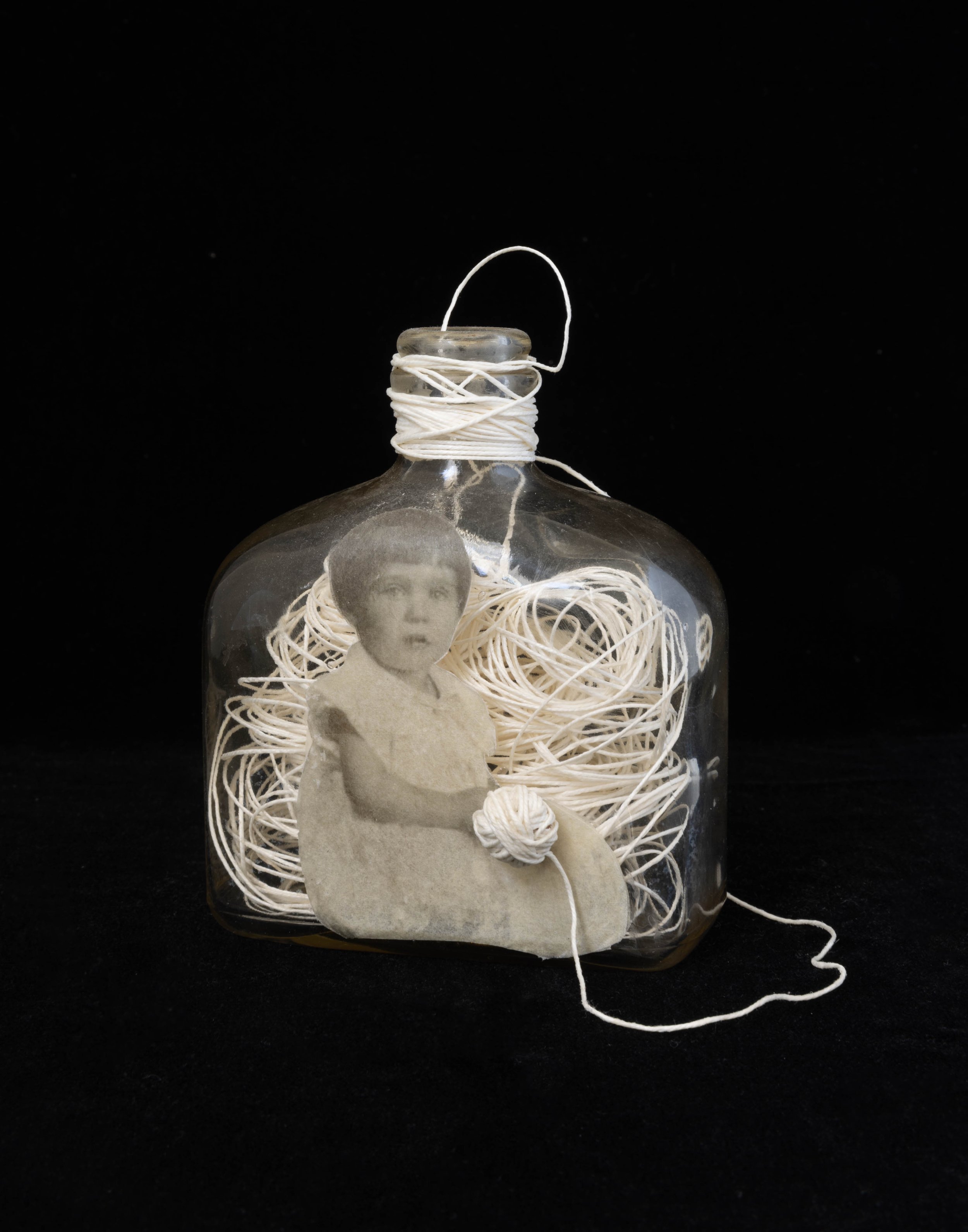

My Aunt Emma was my mother’s sister, who out of eight children, was the only one that never married nor had children. I was told that she had a long-term boyfriend when she was in her twenties whom she wanted to marry, but my grandparents forbid it because he was not Catholic.

My aunt became the caregiver for my grandparents, living at home with them well into her 50’s until they both passed away. Because of the circumstances of her life, so many of her dreams and aspirations were put on hold, bottled up and placed on a shelf never to be realized because of cultural roles and expectations. It wasn’t until I was a young adult that I learned to appreciate the extreme sacrifice my Aunt Emma made to put her life on hold for family.

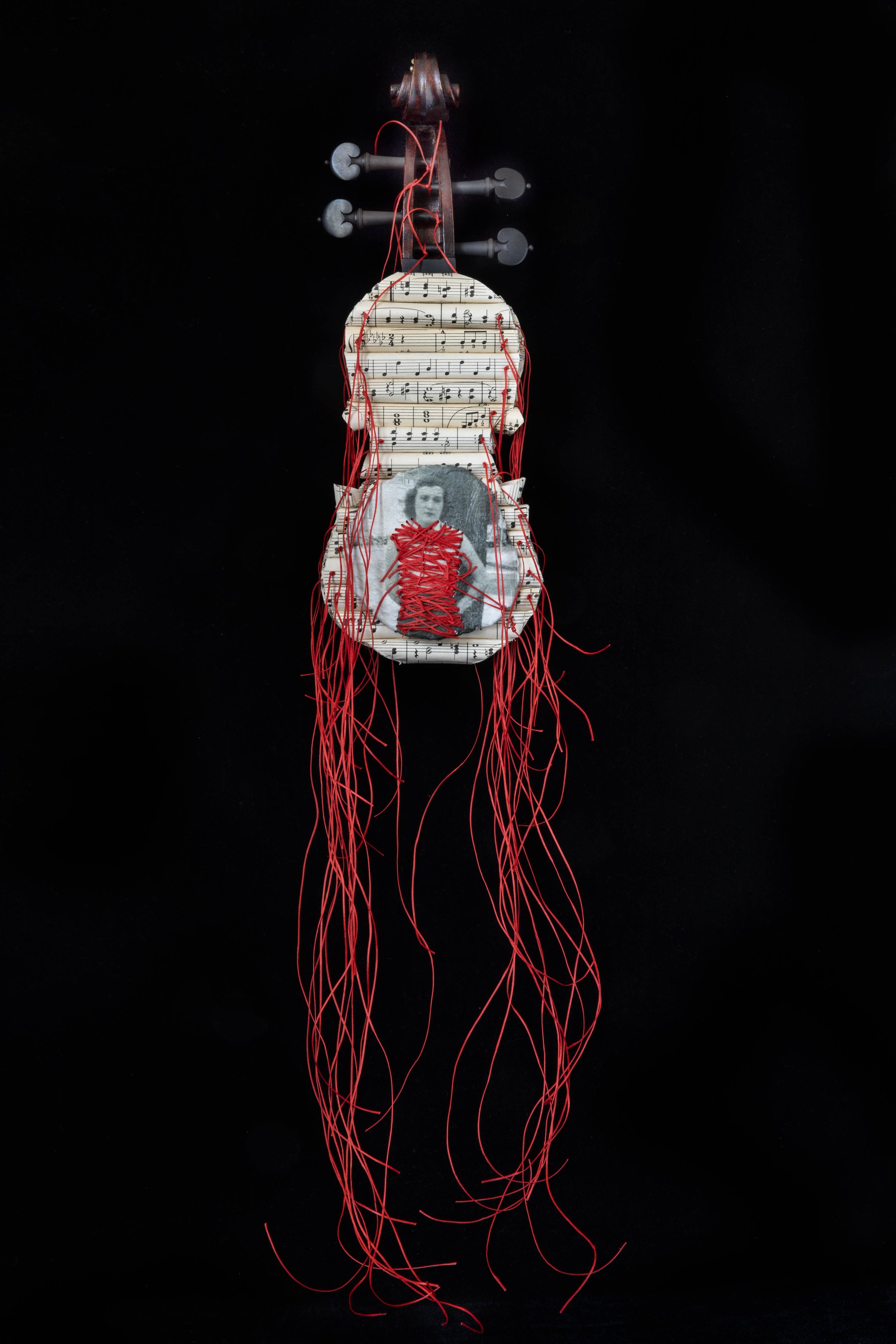

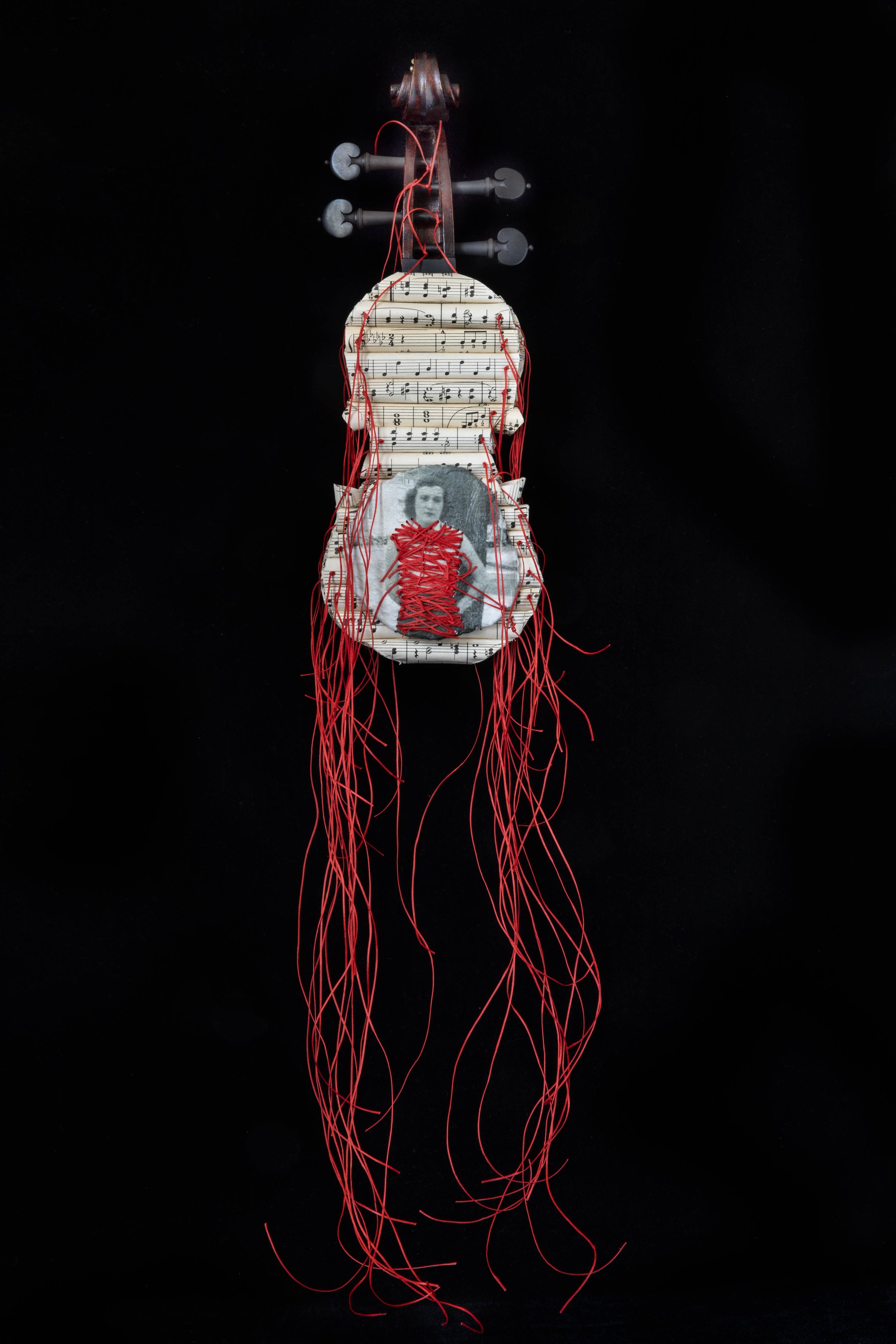

My parents divorced when I was only eight. It was a long-drawn-out bitter divorce that had permanent lasting scars on our family. My mother held on to her bitterness for decades, as if it were a comforting blanket which slowly unraveled as she lashed out at family, ultimately alienating herself from everyone. She was a broken, tattered woman, restrained by her circumstances. My mother enjoyed playing the violin, only to be ridiculed by my father, causing her to stop playing, lock it in its case and placed on the bottom shelf of our family’s closet–never to be opened again. She found happiness by obsessively collecting violin tchotchkes and loved blaring classical music and Italian operas on her stereo.

My Mother’s Song pays homage to my mother, her love of classical music, the violin and the circumstances of a broken marriage that bound her life from ever being truly happy.

My Aunt Ann was my mother’s oldest sister, who became the matriarch of our family once my grandmother passed away. She worked for decades as a seamstress in a sewing factory in Pennsylvania and was my mother’s only sister who moved from NJ. Aunt Ann lived for her family and would never miss any family function in NJ. Her brothers and sisters would always invite her and her husband to stay with them whenever she came to NJ. Yet, she always chose to stay with my mother because they shared a special bond. The kindest, gentlest, caring, and most loving woman, my aunt warmed our entire family’s hearts. Aunt Ann loved to dance and was always one of the first people on the dance-floor during weddings and anniversary celebrations. For many years she suffered from diabetes and later in life lost both her legs to the disease. In order to extend her life, deciding to amputate her legs was one of the most difficult decisions she and her family had to make. Everyone in our family would have done anything within our power to mend her legs and make them healthy and whole.

Mend is an expression of love for my Aunt Ann, it’s a way to use my creative power to reverse the trajectory and make my aunt’s legs whole again. The assemblage uses the foundation of memory and looks at our relationship with the family archive and how it serves as a memorial function.

Some would say a circle is the most perfect geometric shape; it withholds all and everything emerges out of it. Without beginning or end, without sides or corners, a circle represents perfection, unity, spirituality and life like no other shape.

My great grandmother, Vincenza immigrated from Italy to America with six young children. Following the death of my great grandfather, she made the long voyage alone for new beginnings and a better opportunity for their children. She settled in an Italian immigrant community along with many people from her village in Central New Jersey. These Italian immigrants were her circle of friends united to support one another.

We all share this experience, creating an intricate circle of people in our lives; our tribe consisting of friends and/or family who are there for us in times of trouble, sorrow, and celebration. Taking an interest and becoming invested in each other’s lives provides a sense of unity, creating shared common threads that bind us to one another. As we continue our journey through life and come to understand the world better, we use the gained knowledge to expand our circle even further.

The Circle uses this geometric form as the foundation to create a new generational portrait of my great grandmother. It represents the resilience of a woman who rather than remain contained within parameters of her circumstances, pushed those boundaries and expanded her circle. Binding the assemblage in thread represents the security and protection felt in the common ground we share between family and friends.

Resemblance to a family member adds a rich layer to our personal identity and is a beautiful reminder that we’re made up of pieces of our descendants who came before us. It’s also a favorite topic of conversation at family gatherings. Without fail, whenever I attend any family function someone always comments on how much I closely resemble my Uncle Raymond, my mother’s youngest brother. I would concur, we share many dominant features of genetic similarity and as I age, it's uncanny how much we look alike.

Using our high school portraits as the foundation, this assemblage serves as building blocks in creating a new genetic portrait that explores our shared DNA and its role in the physical appearance of an uncle/nephew relationship.

All things have a natural life cycle, and often, they must come to an end to make way for new beginnings.

The influence of my maternal family has played a significant role in shaping and contributing to the formation of our family's identity. As a memory custodian and artist, I feel an unspoken obligation to help preserve the visual history of our family. The contrast between the different generations serves as a poignant reminder that just as individual lives are transient, the legacy of family endures—a continuum of love, lessons, and shared experiences.

The assemblage speaks to the interconnectedness of family history, with each image serving as a snapshot of everyday moments that have shaped our familial journey. It symbolizes a reflection on the transience of individual lives and aging memories, ultimately contributing to the enduring legacy of family.

Aunt Rita was my godmother and my mother’s youngest sister. I adored my Aunt Rita, it was hard not to, everyone loved her because of her warm heart, humor, and vivacious personality. She was a beautiful woman and looked like a starlet when she was young, turning heads whenever she walked into a room. She was the life of any family party and people gravitated towards her because of her infectious personality. She was always surrounded with love and laughter. Later in life, she suffered from Alzheimer’s and dementia, causing her memories to blur and eventually fade. Yet her memory lives strong with our family as big smiles and laughter fill the room whenever her name is mentioned.

While memories help make up our personal identities, they are not static, they are fluid, changing over time. They are influenced by emotions, subconscious biases, pre-conceived ideas, and fade as we grow older. This assemblage is an adoration to my beautiful godmother who left a lasting impression on my life. It uses the foundation of memory and looks at our relationship with the family archive and how it serves as a memorial function.

Faith is considered one of the seven heavenly virtues; and was also a virtue that made up the core of my Aunt Helen’s existence. My aunt was my mother’s older sister, she was a devout Catholic, who had a deep adoration for the church and lived by its teachings as her guiding principles. Aunt Helen was the pillar of her family, she was considered the peacemaker, always smiling, surrounded with positive light and affirmation. Our family jokes that she loved to give papal blessings to her grandchildren as if she were a pint-sized pontiff. Of all my mother’s siblings, she lived the longest, just days of her 90th birthday.

Inspired by Roman Catholic reliquary and ornamentation, Virtue is an expression of admiration for my Aunt Helen and her deep devotion to her faith and love of family.

Our names are a crucial part of our identities. It’s what people call us, what we respond to, it’s what we understand about ourselves. From the day we are born, we are assigned this identifier.

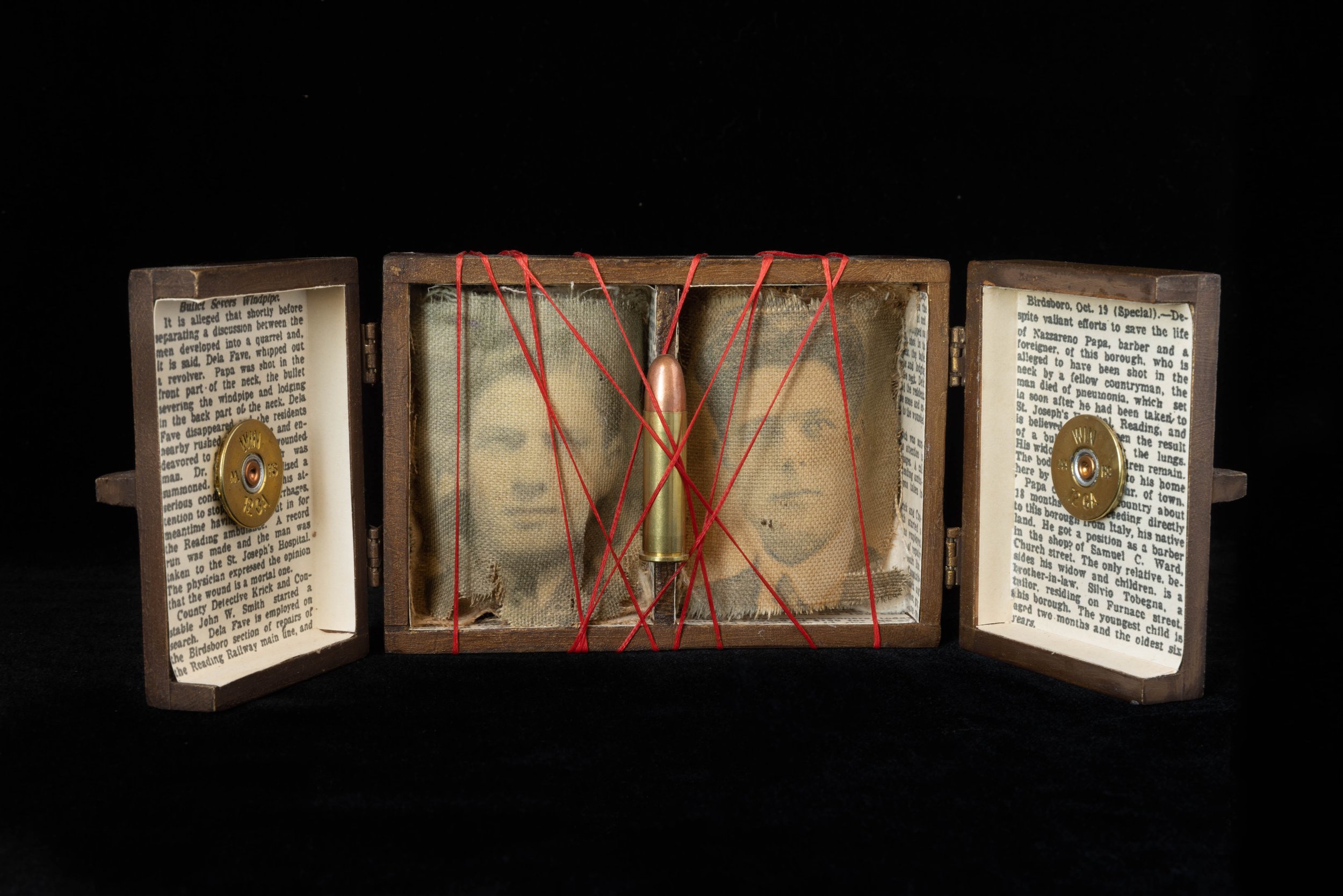

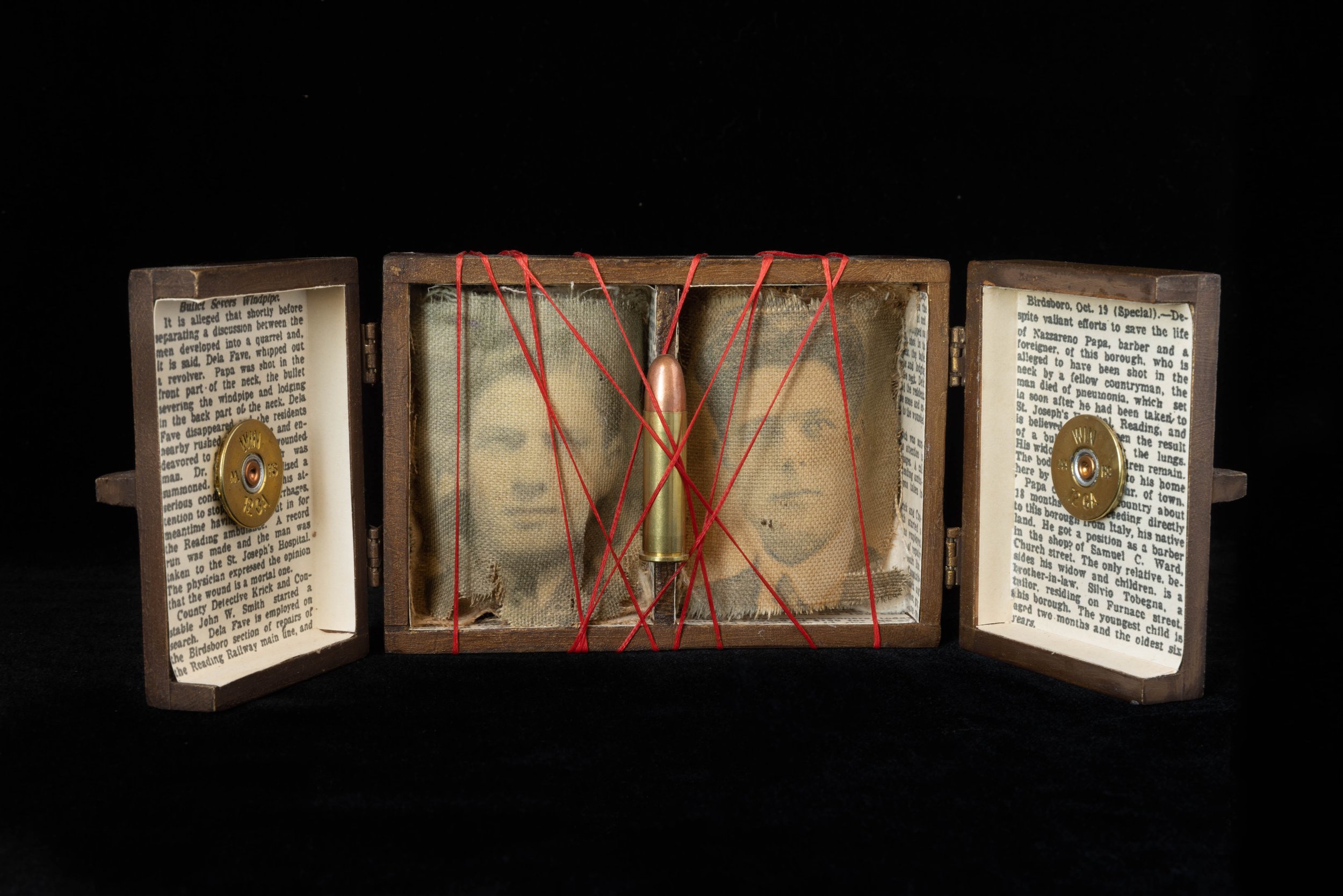

My Uncle Nazz, (short for Nazzareno), was my mother’s oldest brother who lived in CA. We seldom saw him, but when Uncle Nazz would visit NJ, our family would always roll out the red carpet, treating him like a celebrity and throwing big parties in his honor. Growing up, I always thought Uncle Nazz had a cool and unique name, never questioning its origins. I was well into my 50’s when I learned my Uncle Nazz (image on left) was named after my grandfather’s brother Nazzareno. My Great Uncle Nazzareno (image on right) was tragically shot and murdered in his twenties after only having recently emigrating to the US. He left behind a wife and four small children ranging from two months to six years. To honor his memory and legacy, my grandfather named his first son Nazzareno, a namesake after his deceased brother to keep his spirit alive. The murder of my great uncle was a subject that was never spoken of in my family because of the pain it brought to my grandfather. It was a topic to best be kept quiet.

A memory box serves as a loving gesture and foundation for this assemblage, lined with the October 19, 1922 newspaper article that reported on the murder of my Great Uncle. While being a namesake is meant to honor the memory of a loved one, in this instance, it also binds together two identities of nephew and uncle connected by tragedy.

My mother was an emotionally abusive woman with undiagnosed mental health issues. She lived in an alternate reality, fabricating stories she believed to be true, causing her to lash out at her immediate family. By creating a world where she controlled the narrative, she could justify her hurtful actions and behavior, which ultimately alienated her from the entire Papa family.

Having been estranged from my mother for most of my adult life, it’s challenging for me to understand why she treated so many people that genuinely loved and supported her, so poorly. Rather than try to find these impossible answers, I’ve learned to accept, forgive, and find compassion for her in an effort to have closure.

The foundation for this assemblage is a vintage handheld yarn winding tool that is typically used for mending. Straight pins are incorporated to represent the mental cruelty, pain, hurt and anguish my mother inflicted directly on her family.

Uncle Al was my mother’s older brother who became the patriarch of the family once my grandfather passed away. He was the family’s version of “The Godfather” with a raspy timbre in his voice, small moustache, toothpick in mouth and a deep-rooted love of family that spanned generations. Uncle Al represented the foundation and strength of our family, and everyone looked up to him. He proudly wore his protective armor as a shield, shedding it whenever any family member needed his guidance, support, validation, assistance, or help. At his core was a gentle, kind, loving and generous man.

Trees shed their protective layer of bark as they grow, exposing new bark underneath allowing the tree to flourish. In the same manner, I use shedding bark as the foundation of this assemblage to celebrate my uncle’s strength and character, while making room for the next generation of memory keepers who represent the continuation of growth for the family.

Most of us have at least one sibling and there is no question that the bond they share is a special one. They provide a link to our past and are the ones most likely to be with us in the future. I seldom speak of my sibling; a younger brother with whom my relationship would be considered more toxic than special.

My younger brother Charlie and I are separated in age by a little over a year. Our relationship is built on a foundation of anger, paranoia, resentment, hostility, jealousy and at times rage. We are polar opposites in both our personalities as well as our physical appearance. As children, we always had a contentious relationship, and as the years went by our distaste for each other grew to be more toxic. As a means of self-preservation and for the well-being of my immediate family, I made the decision decades ago to sever the relationship with my brother due to his aggressive and unpredictable behavior.

Although Charlie and I have the shared experience of being subjected to our parent’s bitter divorce, and decades of emotional abuse that followed, the outcome of who we’ve become is completely different. Living with untreated mental health conditions combined with substance abuse, my brother developed a dependency for my mother Eva from which he could not break free. Charlie remained emotionally tethered to my mother, living together in our childhood home his entire life until she passed away when he was well into his fifties. It was only then when he was forced to move out on his own and learn to take care of himself. Having removed myself from their dysfunctional family dynamic long ago, it was clear to see my brother and mother enabled one another. Together, they created a world where they justified their hurtful actions and behavior, which ultimately alienated them both from the entire family.

As the foundation for this assemblage, torn words and nails serve as painful reminders of an unmendable severed sibling relationship. They also serve as the physical manifestation of the invisible scars left behind from a lifetime endured of mental cruelty combined with physical and verbal abuse.

Jackie, my goddaughter, is the child of my first cousin, who played a role in caring for me during my infancy. Since her birth, Jackie has been an integral presence in my life, spending many summers with my family during her teenage years, and continuing to hold a cherished role in my life even now that she is a mother. I often playfully remind her that she'll be the one delivering my eulogy when the time comes. Jackie is like a precious jewel, occupying a unique and profound space in my heart. She chose me as her godparent, entrusting me with the privilege and responsibility of cherishing and protecting her.

“The Jewel Within” explores the concept of guardianship and the role of the godparent. It encourages us to recognize the obligation we have to safeguard and treasure those we hold dear like a precious jewel. Incorporating stitched words, this assemblage symbolizes the intricate familial connections, bonds, and interwoven relationships that contribute to a broader narrative of shared experiences within a family.

As a symbol across many cultures, feathers represent a connection to spiritual realms and divinity, signifying protection, love, comfort, and warmth. They are indicative of someone special watching lovingly over us.

Sixteen years my senior, Gloria is my eldest cousin, and our mothers were close sisters. Even with this significant age difference, out of all my relatives, I share the strongest and deepest bond with her. The summer I was born, Gloria stayed with my mother and cared for her because of the complication of toxemia encountered during the pregnancy. Gloria was one of the first people to hold me as an infant when I came home from the hospital, and she helped care for me until my mother recovered. Studies on infant bonding have shown how an infant can experience a strong sense of unconditional love and closeness with relatives outside of their own parents. There is no denying that Gloria has a special place in my heart, and she has always been a significant part of my life, sharing laughter, joy, love, and tears. I strongly believe that in a previous life Gloria and I were bonded as sister and brother.

The use of feathers as the foundation of this assemblage is to signify the protection and preservation of an unbroken bond and transcendent love that is shared in a relationship between two first cousins. The pillow laid upon the softness of the feathers conveys the warmth of the relationship and how it provides comfort to one another.

Those close to me know I have very strong bonds with many of my sixteen first cousins. My cousins are an essential part of the family dynamic. They provide me with something I didn’t always have with my own immediate family, a sense of connection and belonging. Each of my cousins are a reminder of our family’s perseverance, will, strength and courage. They are the glue that holds our families together on an intergenerational level.

My cousin Paulette is my godmother’s daughter – our mothers were sisters. We’ve always had a close bond and been each other’s support system. We’ve witnessed every version of each other; the child, the teen, the adult, the spouse, the parent and now grandparent. Even though a few years separate us, we seem to be living parallel lives. Paulette and I always refer to one another as the male/female versions of each other. This statement is true because the two of us are interchangeable. We have very similar personalities, mannerisms and quirks. So much so, even our children enjoy calling it out and poking fun at us.

Distilling our portraits down to interchangeable pixelated color blocks, this assemblage serves as a means of intertwining our individual identities into one combined collective representation of us both.

What are the odds of three sisters born several years apart having the shared experience of being pregnant simultaneously and all giving birth to boys?

The experience of trying to get pregnant can be all consuming, filled with anxiety and mixed emotions especially when pregnancy deviates from the normal birth-order roles within your family. My mother was the last of her three older sisters and one younger sister to experience motherhood. For several years, she dreamed of being a mother but was unable to conceive. My parents decided to adopt a child and were in the final stages of adopting a baby girl, when they learned the news, my mother was pregnant with me, resulting in them never finalizing the adoption. Not only would my mother be giving birth to her first child, but she would also be sharing the experience of pregnancy simultaneously with her older and younger sister, both of whom were expecting their last child. I was born in 1962, along with my two cousins Jimmy and Michael – all within a few months of one another. We grew up together, we were raised in similar settings with similar backgrounds, shared the same milestones, core values and the three of us are close. Yet our birth order hierarchy within our respective families and role expectations within the birth order are each unique and have contributed to the shaping of our individual personalities and differences in character.

Food has always been an expression of love in my family. Typically, whenever you visited any of my relatives, the first thing out of their mouth was, “Did you eat?” Meals were magic, they created the bond that brought together and united our extended family.

Somewhat of a talisman, the handwritten family recipe holds significance. In my family, it has become one of the most cherished inheritances to be handed down through the generations. Seeing the handwritten script of a loved one is an iconic memory that immediately triggers the sensory recall to the wonderful warm memories made in the kitchen. Secret ingredients revealed, stories were told, and family traditions shared, all took place in the kitchen – truly the heart of the home.

The foundation for this assemblage is a vintage ravioli roller. The assemblage melds together three past generations of Papa women who were instrumental in sharing their love for the family meal, their homemade recipes, and a piece of their legacy to be passed down and experienced with the younger and future generations of Papa’s. While each of the Papa women stand alone in their separate squares, the overall effect of bringing them together is to represent how they each played a role in creating the Papa history and traditions our family shares today.

Tables are designed to provide support and serve as a destination point, but they can also be so much more. In most homes, the kitchen table is a timeless symbol of unity and connection. The table serves as a beacon bringing families together, fostering an environment where loved ones can gather, reconnect, and bond over a shared meal.

Growing up, Sunday was typically the designated day our family would gather at the home of my grandparents. While their kitchen table was often a place for various forms of nourishment, it also served many functions in our family. The table served as a conduit, where many of the Papa traditions and memories were born and passed down through generations. It was an art table, where my grandmother used to teach me how to draw chickens and roosters on scratch pieces of paper. At times it served as an altar, being the place where the Italian malocchio ritual was performed – a ritual consisting of oil, water and silent prayer to rid a family member of the “evil eye”. Most of my family photos are of family members gathered around my grandparent’s kitchen table in celebration of a special day or life event, making their kitchen the most photographed room in the home.

The foundation for this assemblage uses a cutting board, plate and utensil, items meant to aid in nourishment. It serves as a reminder that the kitchen table is not merely a piece of furniture, but a scared place to cherish. A place to create traditions and memories, where relationships are nourished, and bonds strengthened uniting us as families.

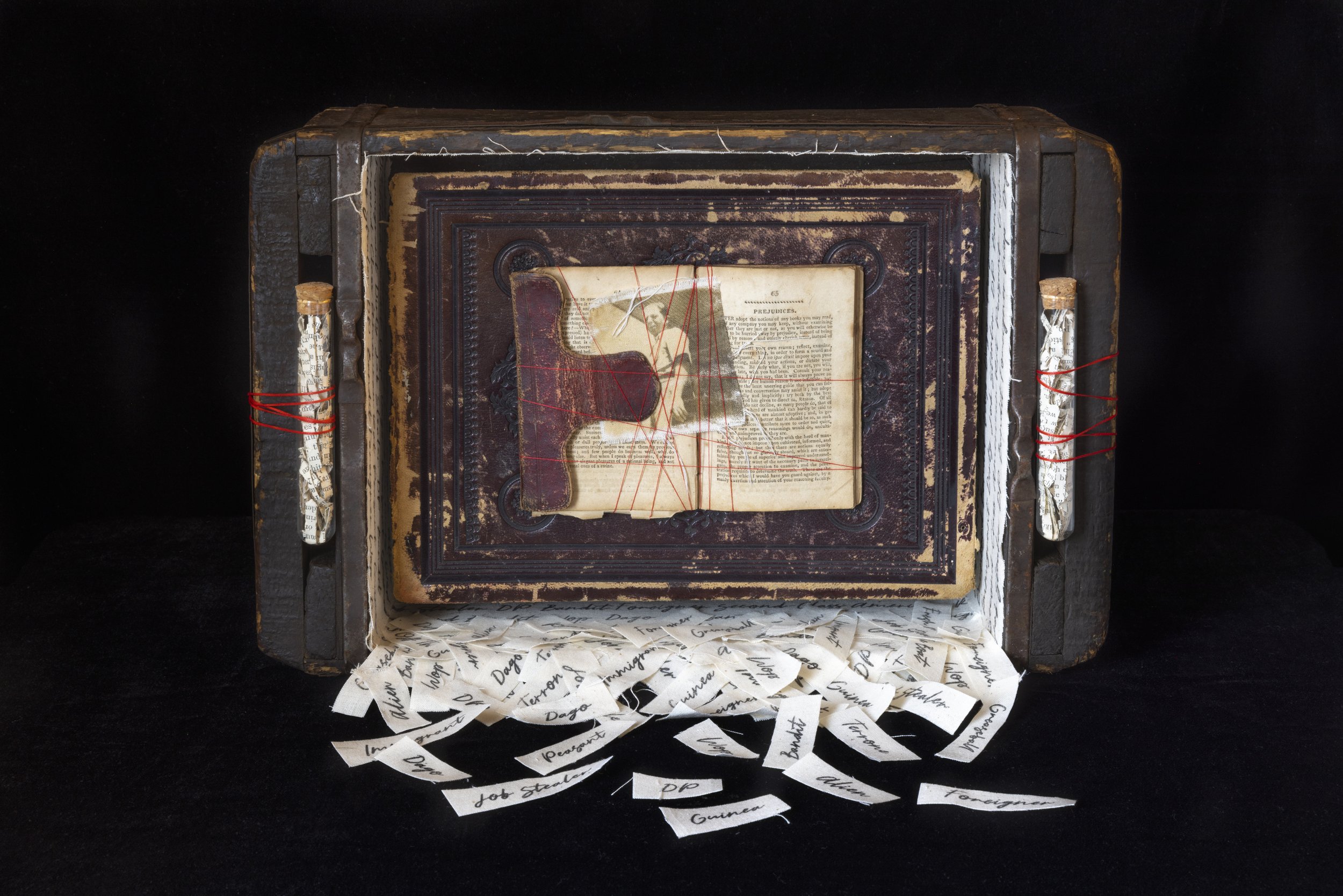

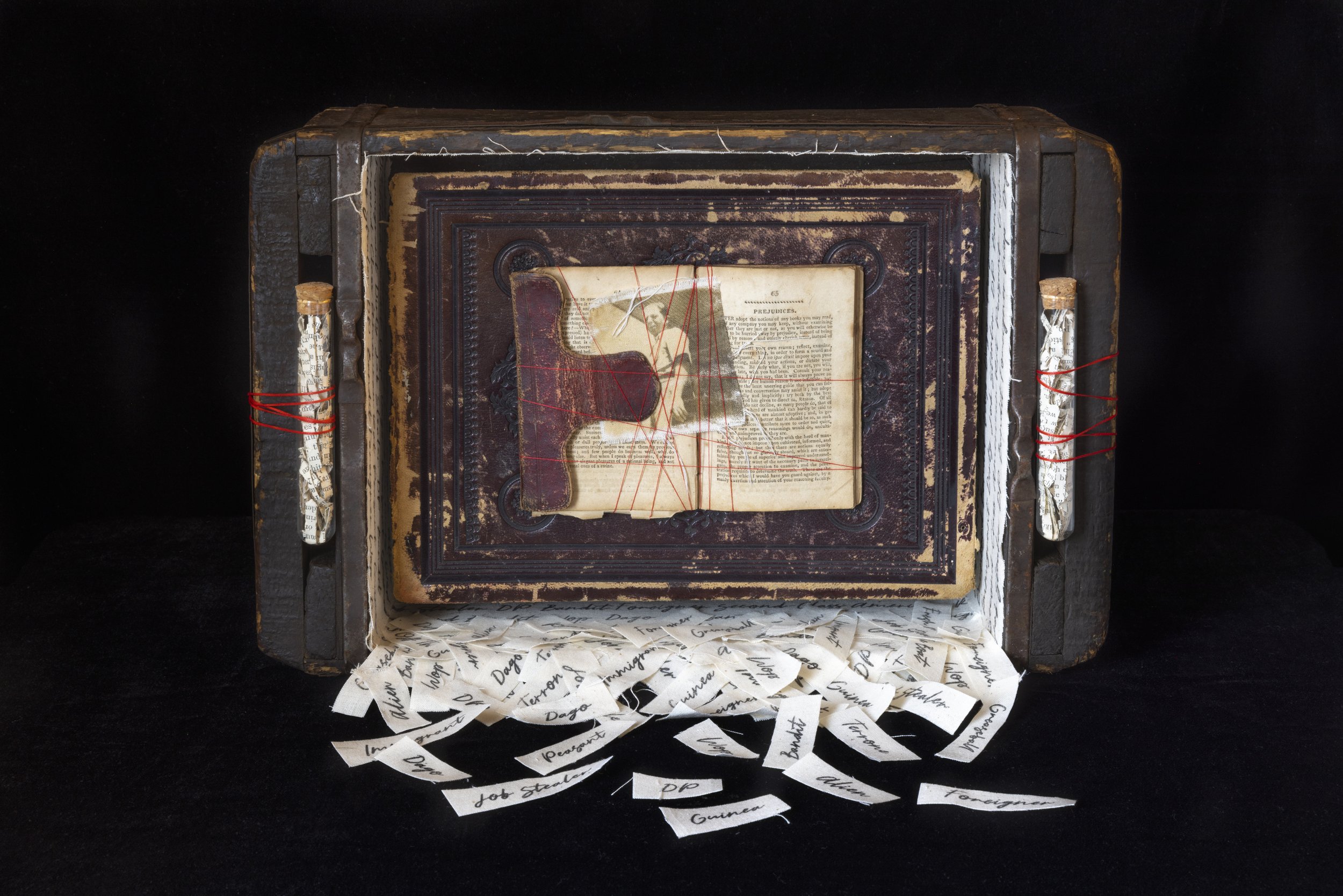

The early 20th-century Italian diaspora faced discrimination and negative stereotypes, with those arriving being unfairly judged based on nationality and encountering systemic hurdles in assimilating into new societies, including barriers to employment, housing, and social acceptance.

My grandfather, aged 27, emigrated from Benevento, Italy, on December 20, 1919, seeking economic opportunities and a new life. Despite his strong work ethic, he struggled with biases and derogatory labels like "Wop, Guinea, Dago, Alien, Immigrant, Foreigner, and DP," hindering his integration. A skilled craftsman and business owner, he faced obstacles from organized crime, making "monthly payments" to maintain his shoemaker shop, and being "swindled" from home ownership. Despite adversity, his survival strategy focused on hard work and family.

This assemblage serves as a narrative of the Italian diaspora and stands as a testament to the resilience of a community that, despite being bound by labels and prejudices, gradually found its place in the mosaic of global cultures.

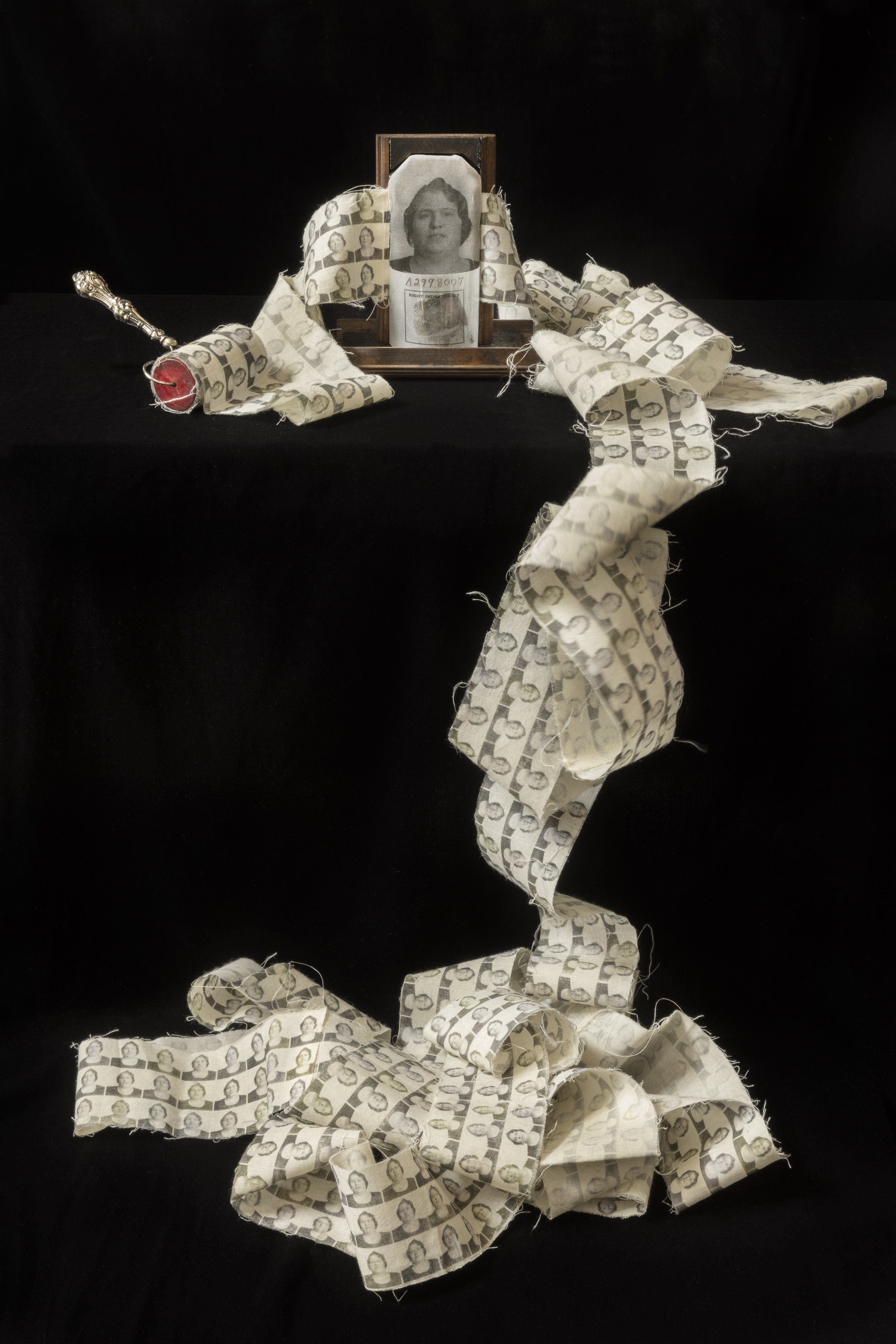

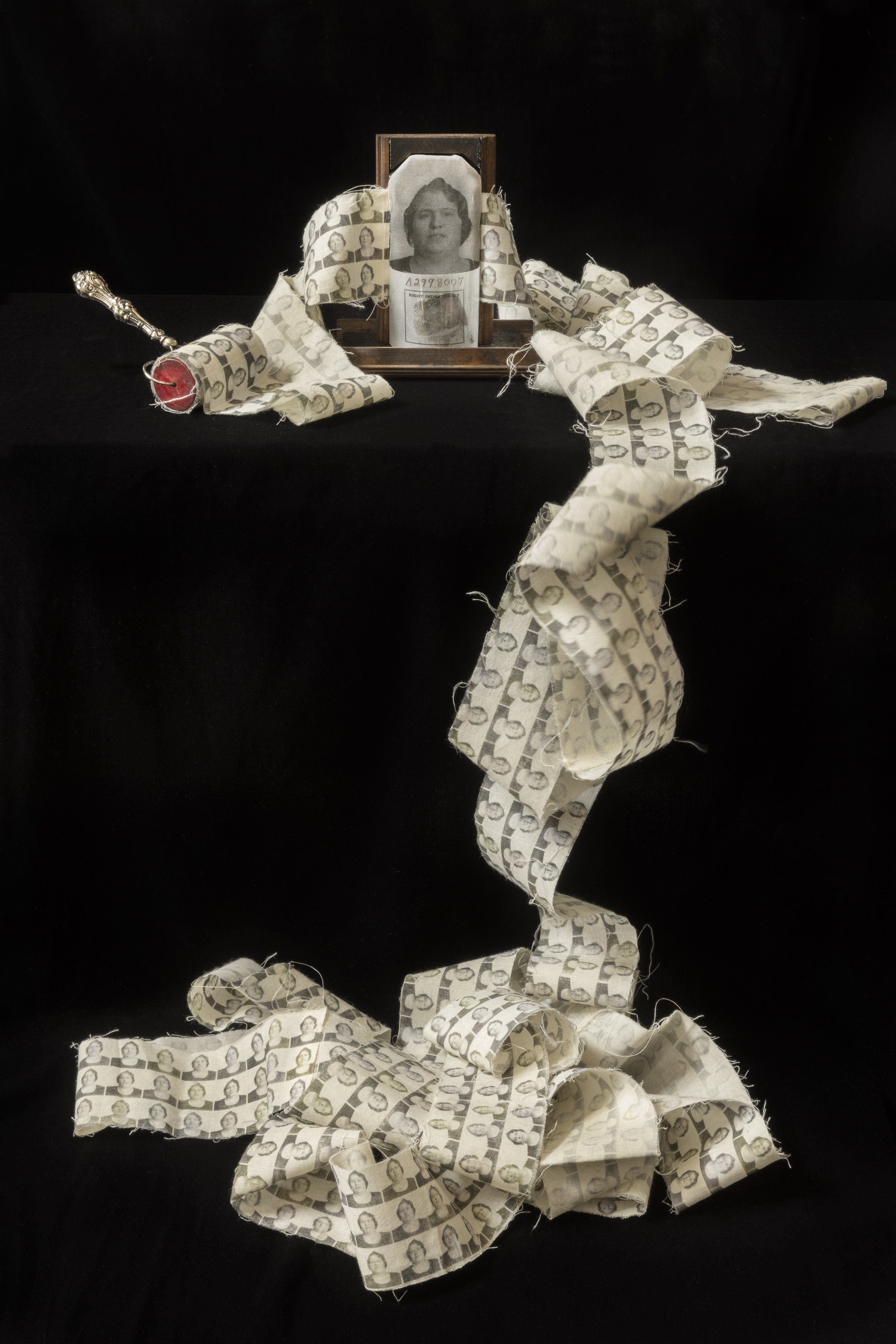

During World War II, the Alien Registration Act of 1940 was implemented, mandating every alien aged 14 and above, including those branded “enemy aliens” from Italy, Germany, and Japan, to register at local post offices upon residing or arriving in the United States. This registration process entailed fingerprinting, photographing, and completion of a set of 15 questions designed to gather personal information and identify potential security risks, resulting in the establishment of a comprehensive database. Within a span of four months, a staggering 5 million aliens had been registered.

My grandfather had attained American citizenship, but my grandmother, who had been living in the United States for twenty years, never acquired citizenship. She was categorized as an "enemy alien", despite being the mother of eight American-born children, two of whom were serving in WWII. The process of complying with the regulations must have been incredibly daunting for her, especially considering her non-native proficiency in English. The fear of misinterpretation or answering questions incorrectly, and the possibility of being deported or imprisoned, must have been overwhelming. Assigned the alien number A2998007, my grandmother's experience reflects the anxieties and challenges faced by many during this turbulent period of history.

A2998007 incorporates a vintage fingerprint kit and ink roller, as well as the photograph and fingerprint of my grandmother that was used in her alien registration form. The assemblage consists of 850 images, each representing 6,000 individuals, symbolizing the 5 million aliens who registered within a four-month timeframe under the Alien Registration Act of 1940.

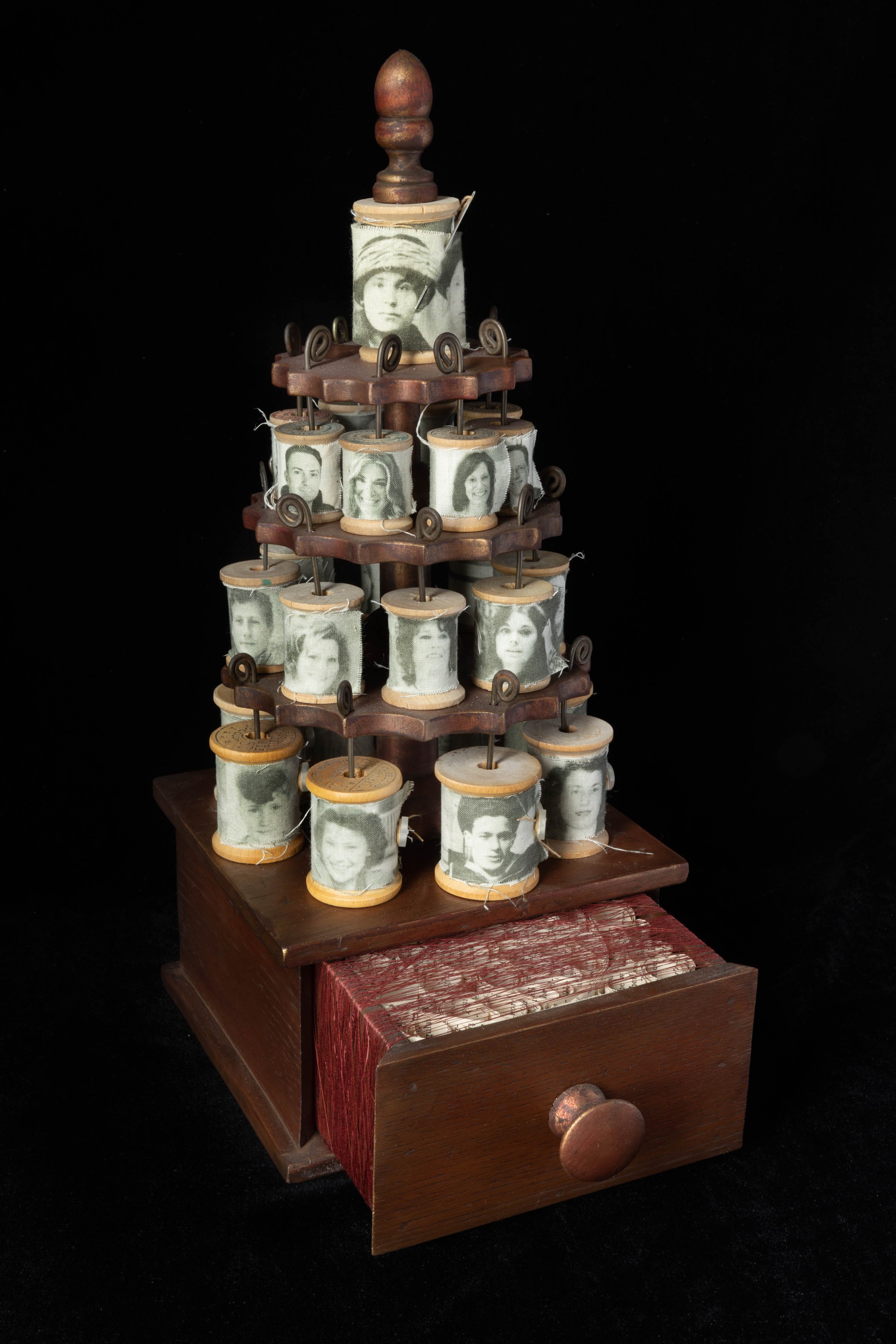

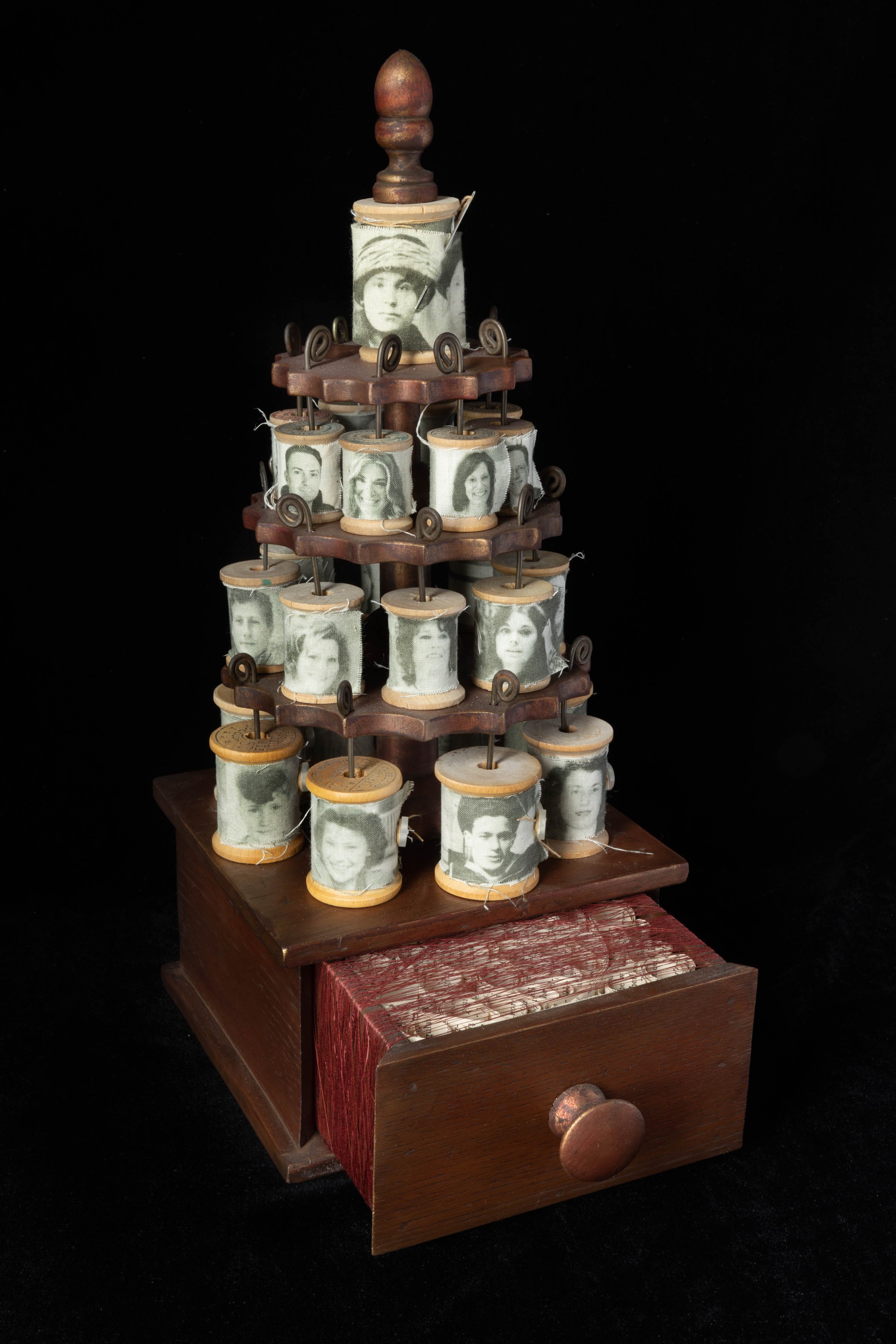

Family is comprised of complex relationships that often become entangled like threads at the bottom of a sewing kit. But when those threads are brought together like the warp and weft of a loom, they create something of substance. In that same manner, the spools represent memories of three generations of Papa consisting of my maternal grandparents, eight aunts and uncles and sixteen first cousins. My generation, consisting of first cousins, serve as the memory keepers for the Papa legacy. With that comes an obligation to preserve the values instilled, the lessons learned, the stories told, and the traditions shared with the new generation of Papa’s. Preserving the Papa history is a declaration of love for those that came before and as a legacy for remembrance to be passed down.

Photographs are prompts for recollection; they are taken in anticipation of forgetting. While this assemblage serves as the anchor piece for the series, its intent is to enhance the object’s capacity to provoke remembrance allowing for the past and the present to cohabit in the everyday.

My grandmother, Annunziata Papa was the glue that bonded our family together. Even though my grandfather was the head of the house, it was my grandmother’s voice that everyone listened to as the final decision. She emigrated from Italy shortly after my grandfather and they were soon married on October 31, 1920. They settled in Central New Jersey and lived in an Italian immigrant community. Like most Italian grandmothers, she was an exceptional cook and earned money by taking in sewing. Her role was to take care of the household, her husband and eight children. She was always surrounded by her family and there was an abundance of love that continuously radiated from her. Grandmom instilled in us strong family values and traditions that have been passed down for generations. I was only nine when she passed, though some memories have faded, the most vivid are the ones of her sitting down at the kitchen table teaching me how to draw chickens and roosters on scratch pieces of paper.

This assemblage is inspired by the notions of sewing and mending. Countless threads represent the interweaving of traditions, values and teachings cocooning my grandmother’s portrait symbolizing the core strength, devotion, resilience, and an unbounding love of family.

My maternal grandfather was the patriarch of our family. He was a shoemaker who owned his own shop. I have fond memories as a child of visiting him at his store in Bound Brook, NJ. The smell of leather as he tapped and stitched with the sunlight streaming through the small front windows, highlighted by the smoke from my grandfather’s cigarette holder. At the end of the visit, my grandfather would always open his work drawer and hand me black licorice candy. The scent and flavor of black licorice is a powerful sensory memory trigger and to this day I love anything flavored with licorice or anise. It’s a comforting feeling that reminds me of my grandfather, Alfredo Papa.

Inspired by the eyelets, hooks and laces of my grandfather’s shop, Alfredo uses the foundation of memory and looks at our relationship with the family archive and how it serves as a memorial function.

My Aunt Emma was my mother’s sister, who out of eight children, was the only one that never married nor had children. I was told that she had a long-term boyfriend when she was in her twenties whom she wanted to marry, but my grandparents forbid it because he was not Catholic.

My aunt became the caregiver for my grandparents, living at home with them well into her 50’s until they both passed away. Because of the circumstances of her life, so many of her dreams and aspirations were put on hold, bottled up and placed on a shelf never to be realized because of cultural roles and expectations. It wasn’t until I was a young adult that I learned to appreciate the extreme sacrifice my Aunt Emma made to put her life on hold for family.

My parents divorced when I was only eight. It was a long-drawn-out bitter divorce that had permanent lasting scars on our family. My mother held on to her bitterness for decades, as if it were a comforting blanket which slowly unraveled as she lashed out at family, ultimately alienating herself from everyone. She was a broken, tattered woman, restrained by her circumstances. My mother enjoyed playing the violin, only to be ridiculed by my father, causing her to stop playing, lock it in its case and placed on the bottom shelf of our family’s closet–never to be opened again. She found happiness by obsessively collecting violin tchotchkes and loved blaring classical music and Italian operas on her stereo.

My Mother’s Song pays homage to my mother, her love of classical music, the violin and the circumstances of a broken marriage that bound her life from ever being truly happy.

My Aunt Ann was my mother’s oldest sister, who became the matriarch of our family once my grandmother passed away. She worked for decades as a seamstress in a sewing factory in Pennsylvania and was my mother’s only sister who moved from NJ. Aunt Ann lived for her family and would never miss any family function in NJ. Her brothers and sisters would always invite her and her husband to stay with them whenever she came to NJ. Yet, she always chose to stay with my mother because they shared a special bond. The kindest, gentlest, caring, and most loving woman, my aunt warmed our entire family’s hearts. Aunt Ann loved to dance and was always one of the first people on the dance-floor during weddings and anniversary celebrations. For many years she suffered from diabetes and later in life lost both her legs to the disease. In order to extend her life, deciding to amputate her legs was one of the most difficult decisions she and her family had to make. Everyone in our family would have done anything within our power to mend her legs and make them healthy and whole.

Mend is an expression of love for my Aunt Ann, it’s a way to use my creative power to reverse the trajectory and make my aunt’s legs whole again. The assemblage uses the foundation of memory and looks at our relationship with the family archive and how it serves as a memorial function.

Some would say a circle is the most perfect geometric shape; it withholds all and everything emerges out of it. Without beginning or end, without sides or corners, a circle represents perfection, unity, spirituality and life like no other shape.

My great grandmother, Vincenza immigrated from Italy to America with six young children. Following the death of my great grandfather, she made the long voyage alone for new beginnings and a better opportunity for their children. She settled in an Italian immigrant community along with many people from her village in Central New Jersey. These Italian immigrants were her circle of friends united to support one another.

We all share this experience, creating an intricate circle of people in our lives; our tribe consisting of friends and/or family who are there for us in times of trouble, sorrow, and celebration. Taking an interest and becoming invested in each other’s lives provides a sense of unity, creating shared common threads that bind us to one another. As we continue our journey through life and come to understand the world better, we use the gained knowledge to expand our circle even further.

The Circle uses this geometric form as the foundation to create a new generational portrait of my great grandmother. It represents the resilience of a woman who rather than remain contained within parameters of her circumstances, pushed those boundaries and expanded her circle. Binding the assemblage in thread represents the security and protection felt in the common ground we share between family and friends.

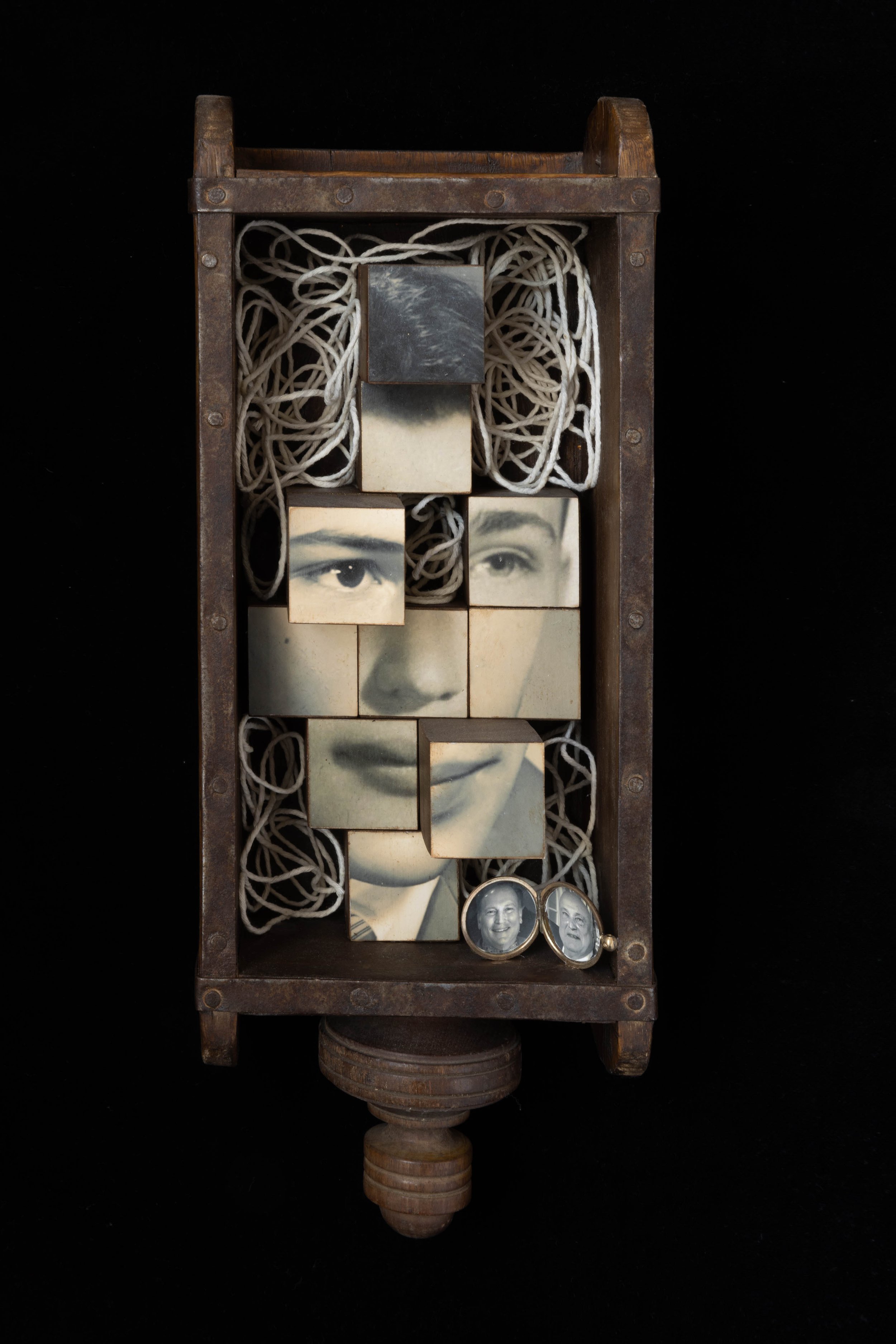

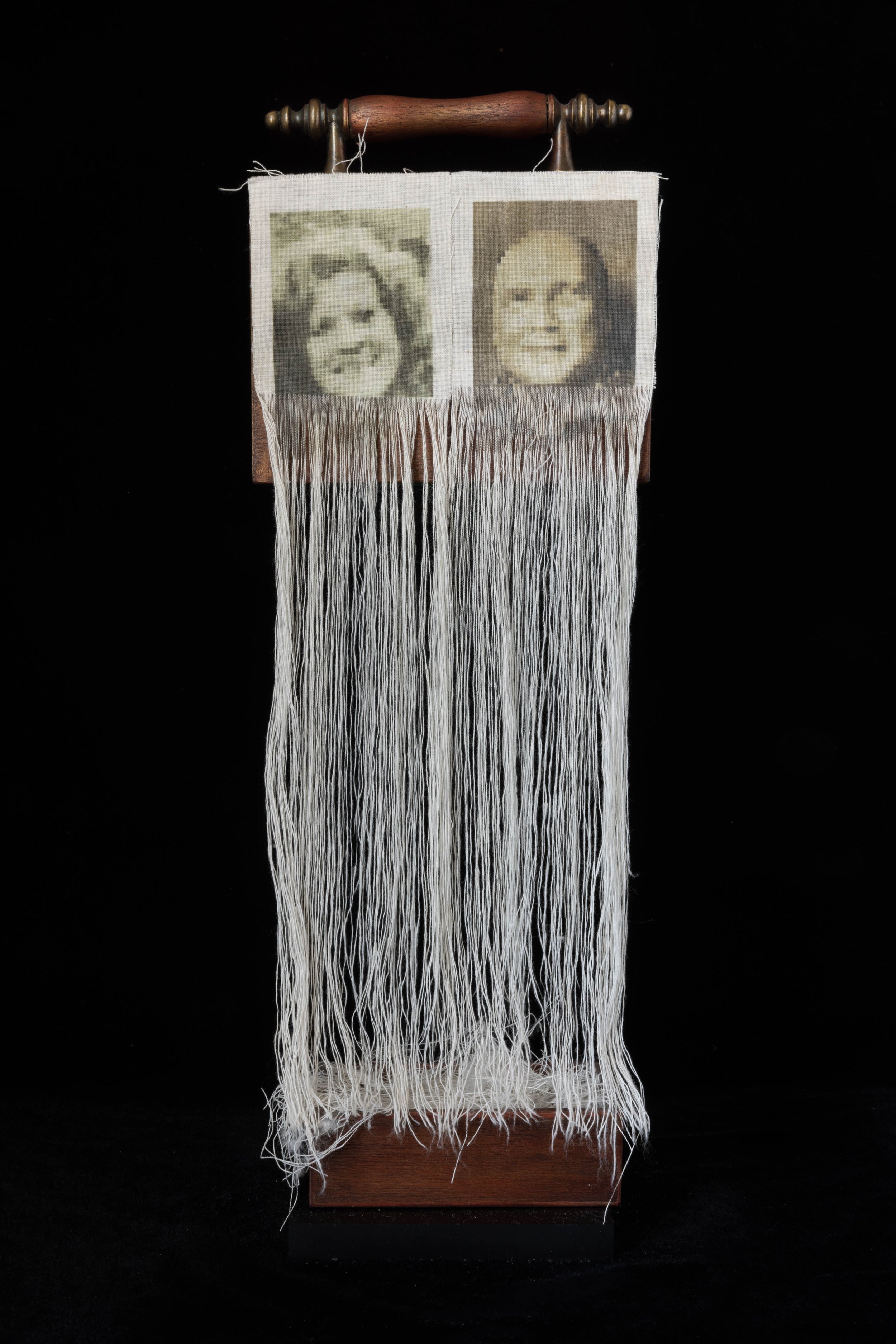

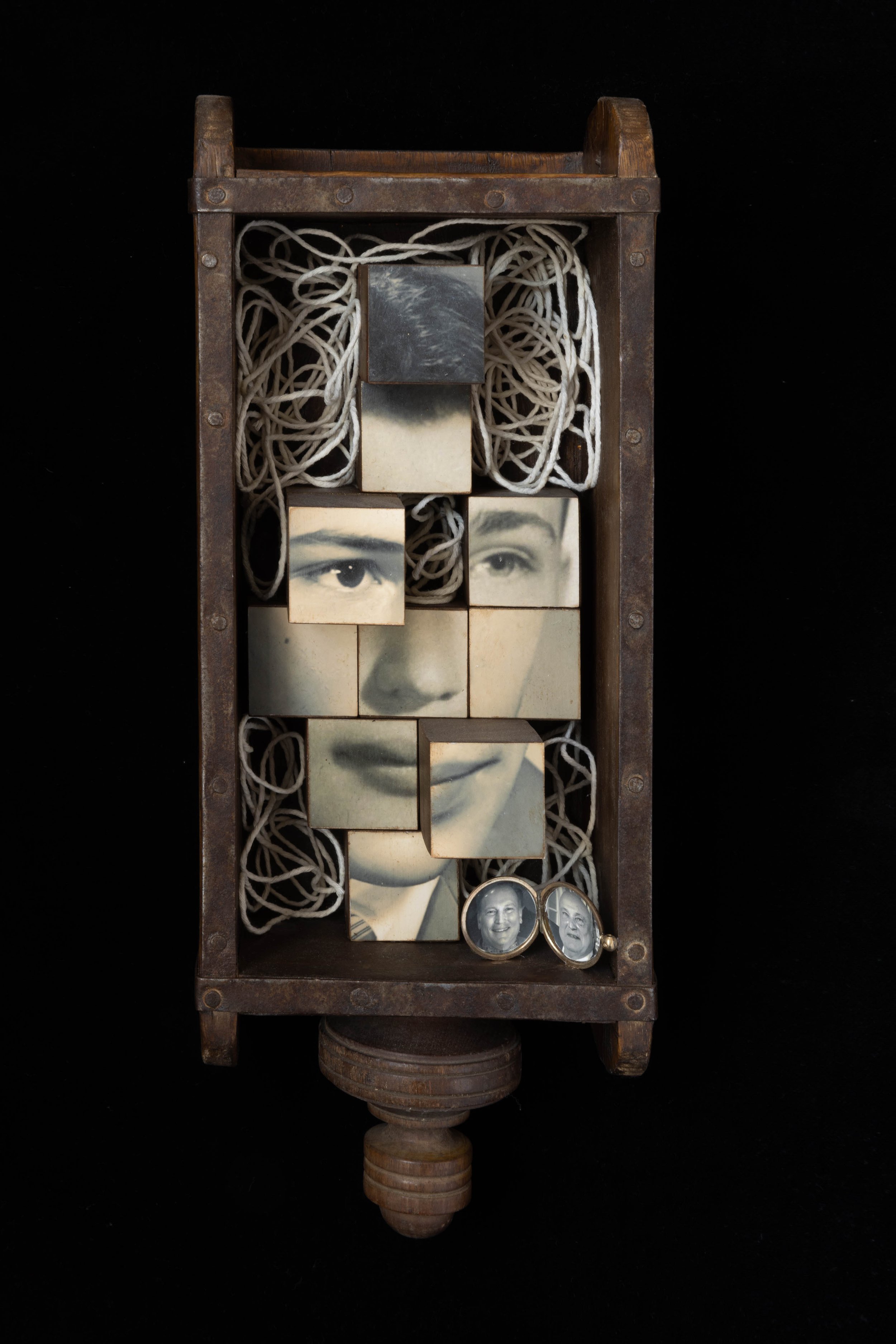

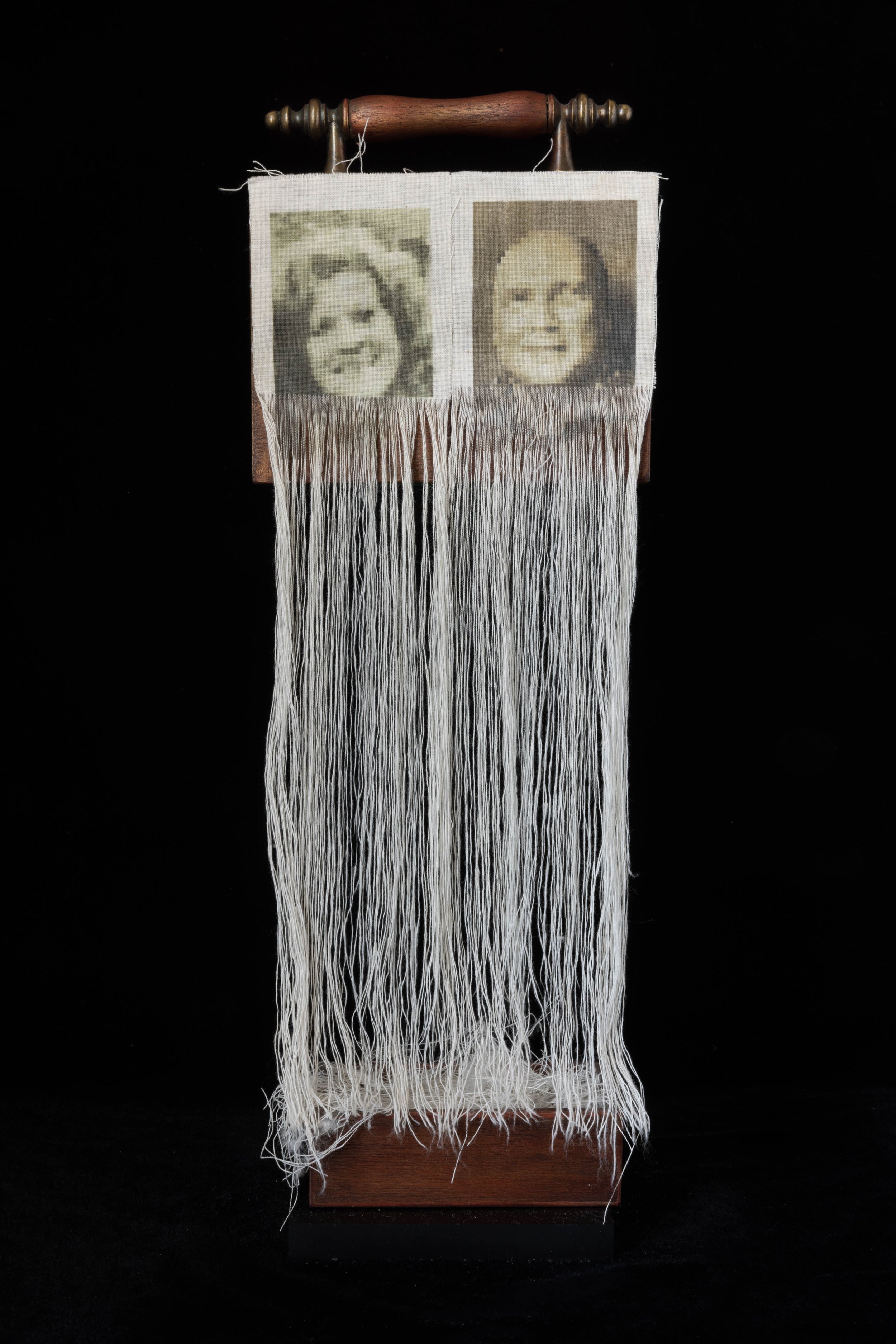

Resemblance to a family member adds a rich layer to our personal identity and is a beautiful reminder that we’re made up of pieces of our descendants who came before us. It’s also a favorite topic of conversation at family gatherings. Without fail, whenever I attend any family function someone always comments on how much I closely resemble my Uncle Raymond, my mother’s youngest brother. I would concur, we share many dominant features of genetic similarity and as I age, it's uncanny how much we look alike.

Using our high school portraits as the foundation, this assemblage serves as building blocks in creating a new genetic portrait that explores our shared DNA and its role in the physical appearance of an uncle/nephew relationship.

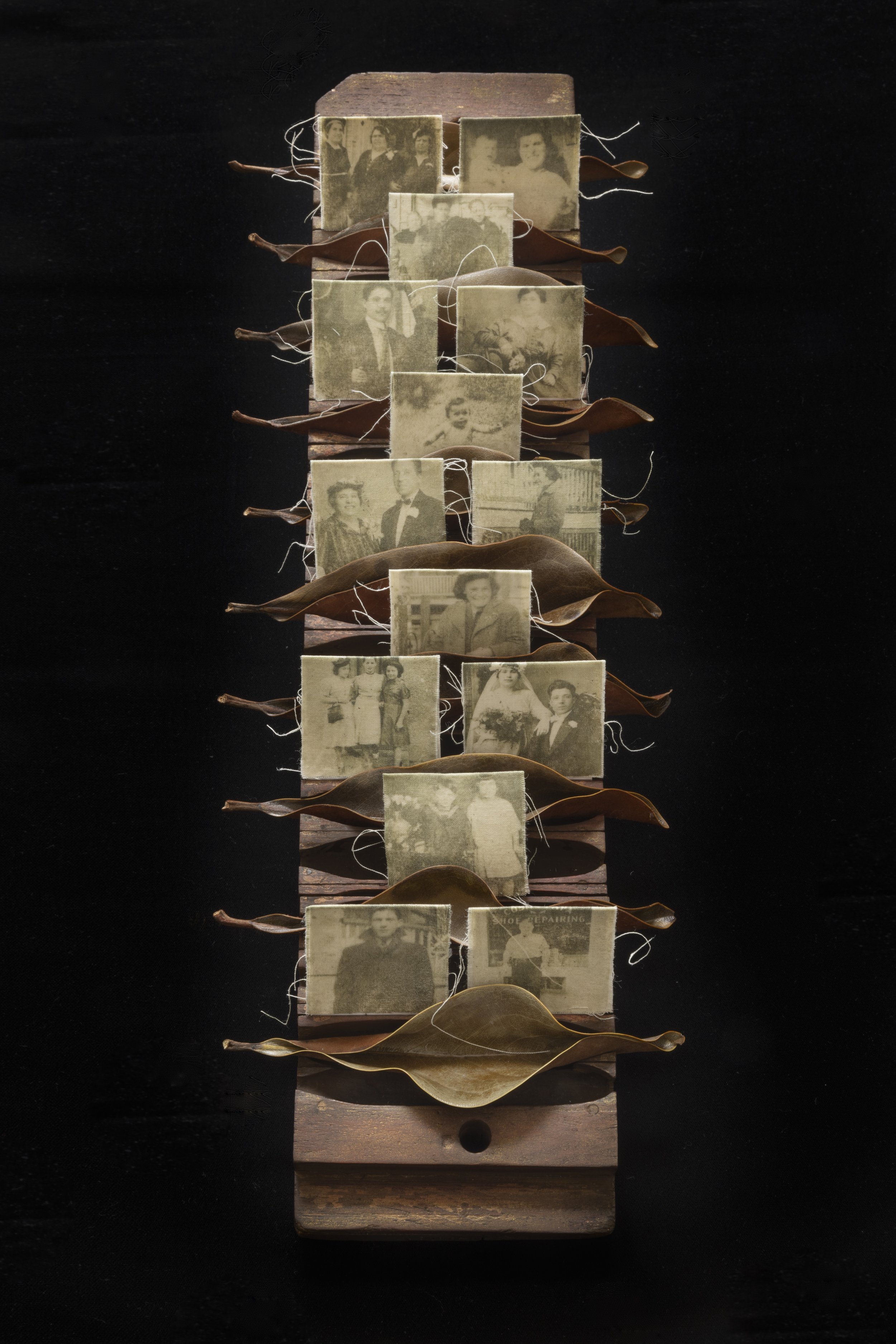

All things have a natural life cycle, and often, they must come to an end to make way for new beginnings.

The influence of my maternal family has played a significant role in shaping and contributing to the formation of our family's identity. As a memory custodian and artist, I feel an unspoken obligation to help preserve the visual history of our family. The contrast between the different generations serves as a poignant reminder that just as individual lives are transient, the legacy of family endures—a continuum of love, lessons, and shared experiences.

The assemblage speaks to the interconnectedness of family history, with each image serving as a snapshot of everyday moments that have shaped our familial journey. It symbolizes a reflection on the transience of individual lives and aging memories, ultimately contributing to the enduring legacy of family.

Aunt Rita was my godmother and my mother’s youngest sister. I adored my Aunt Rita, it was hard not to, everyone loved her because of her warm heart, humor, and vivacious personality. She was a beautiful woman and looked like a starlet when she was young, turning heads whenever she walked into a room. She was the life of any family party and people gravitated towards her because of her infectious personality. She was always surrounded with love and laughter. Later in life, she suffered from Alzheimer’s and dementia, causing her memories to blur and eventually fade. Yet her memory lives strong with our family as big smiles and laughter fill the room whenever her name is mentioned.

While memories help make up our personal identities, they are not static, they are fluid, changing over time. They are influenced by emotions, subconscious biases, pre-conceived ideas, and fade as we grow older. This assemblage is an adoration to my beautiful godmother who left a lasting impression on my life. It uses the foundation of memory and looks at our relationship with the family archive and how it serves as a memorial function.

Faith is considered one of the seven heavenly virtues; and was also a virtue that made up the core of my Aunt Helen’s existence. My aunt was my mother’s older sister, she was a devout Catholic, who had a deep adoration for the church and lived by its teachings as her guiding principles. Aunt Helen was the pillar of her family, she was considered the peacemaker, always smiling, surrounded with positive light and affirmation. Our family jokes that she loved to give papal blessings to her grandchildren as if she were a pint-sized pontiff. Of all my mother’s siblings, she lived the longest, just days of her 90th birthday.

Inspired by Roman Catholic reliquary and ornamentation, Virtue is an expression of admiration for my Aunt Helen and her deep devotion to her faith and love of family.

Our names are a crucial part of our identities. It’s what people call us, what we respond to, it’s what we understand about ourselves. From the day we are born, we are assigned this identifier.

My Uncle Nazz, (short for Nazzareno), was my mother’s oldest brother who lived in CA. We seldom saw him, but when Uncle Nazz would visit NJ, our family would always roll out the red carpet, treating him like a celebrity and throwing big parties in his honor. Growing up, I always thought Uncle Nazz had a cool and unique name, never questioning its origins. I was well into my 50’s when I learned my Uncle Nazz (image on left) was named after my grandfather’s brother Nazzareno. My Great Uncle Nazzareno (image on right) was tragically shot and murdered in his twenties after only having recently emigrating to the US. He left behind a wife and four small children ranging from two months to six years. To honor his memory and legacy, my grandfather named his first son Nazzareno, a namesake after his deceased brother to keep his spirit alive. The murder of my great uncle was a subject that was never spoken of in my family because of the pain it brought to my grandfather. It was a topic to best be kept quiet.

A memory box serves as a loving gesture and foundation for this assemblage, lined with the October 19, 1922 newspaper article that reported on the murder of my Great Uncle. While being a namesake is meant to honor the memory of a loved one, in this instance, it also binds together two identities of nephew and uncle connected by tragedy.

My mother was an emotionally abusive woman with undiagnosed mental health issues. She lived in an alternate reality, fabricating stories she believed to be true, causing her to lash out at her immediate family. By creating a world where she controlled the narrative, she could justify her hurtful actions and behavior, which ultimately alienated her from the entire Papa family.

Having been estranged from my mother for most of my adult life, it’s challenging for me to understand why she treated so many people that genuinely loved and supported her, so poorly. Rather than try to find these impossible answers, I’ve learned to accept, forgive, and find compassion for her in an effort to have closure.

The foundation for this assemblage is a vintage handheld yarn winding tool that is typically used for mending. Straight pins are incorporated to represent the mental cruelty, pain, hurt and anguish my mother inflicted directly on her family.

Uncle Al was my mother’s older brother who became the patriarch of the family once my grandfather passed away. He was the family’s version of “The Godfather” with a raspy timbre in his voice, small moustache, toothpick in mouth and a deep-rooted love of family that spanned generations. Uncle Al represented the foundation and strength of our family, and everyone looked up to him. He proudly wore his protective armor as a shield, shedding it whenever any family member needed his guidance, support, validation, assistance, or help. At his core was a gentle, kind, loving and generous man.

Trees shed their protective layer of bark as they grow, exposing new bark underneath allowing the tree to flourish. In the same manner, I use shedding bark as the foundation of this assemblage to celebrate my uncle’s strength and character, while making room for the next generation of memory keepers who represent the continuation of growth for the family.

Most of us have at least one sibling and there is no question that the bond they share is a special one. They provide a link to our past and are the ones most likely to be with us in the future. I seldom speak of my sibling; a younger brother with whom my relationship would be considered more toxic than special.

My younger brother Charlie and I are separated in age by a little over a year. Our relationship is built on a foundation of anger, paranoia, resentment, hostility, jealousy and at times rage. We are polar opposites in both our personalities as well as our physical appearance. As children, we always had a contentious relationship, and as the years went by our distaste for each other grew to be more toxic. As a means of self-preservation and for the well-being of my immediate family, I made the decision decades ago to sever the relationship with my brother due to his aggressive and unpredictable behavior.

Although Charlie and I have the shared experience of being subjected to our parent’s bitter divorce, and decades of emotional abuse that followed, the outcome of who we’ve become is completely different. Living with untreated mental health conditions combined with substance abuse, my brother developed a dependency for my mother Eva from which he could not break free. Charlie remained emotionally tethered to my mother, living together in our childhood home his entire life until she passed away when he was well into his fifties. It was only then when he was forced to move out on his own and learn to take care of himself. Having removed myself from their dysfunctional family dynamic long ago, it was clear to see my brother and mother enabled one another. Together, they created a world where they justified their hurtful actions and behavior, which ultimately alienated them both from the entire family.

As the foundation for this assemblage, torn words and nails serve as painful reminders of an unmendable severed sibling relationship. They also serve as the physical manifestation of the invisible scars left behind from a lifetime endured of mental cruelty combined with physical and verbal abuse.

Jackie, my goddaughter, is the child of my first cousin, who played a role in caring for me during my infancy. Since her birth, Jackie has been an integral presence in my life, spending many summers with my family during her teenage years, and continuing to hold a cherished role in my life even now that she is a mother. I often playfully remind her that she'll be the one delivering my eulogy when the time comes. Jackie is like a precious jewel, occupying a unique and profound space in my heart. She chose me as her godparent, entrusting me with the privilege and responsibility of cherishing and protecting her.

“The Jewel Within” explores the concept of guardianship and the role of the godparent. It encourages us to recognize the obligation we have to safeguard and treasure those we hold dear like a precious jewel. Incorporating stitched words, this assemblage symbolizes the intricate familial connections, bonds, and interwoven relationships that contribute to a broader narrative of shared experiences within a family.

As a symbol across many cultures, feathers represent a connection to spiritual realms and divinity, signifying protection, love, comfort, and warmth. They are indicative of someone special watching lovingly over us.

Sixteen years my senior, Gloria is my eldest cousin, and our mothers were close sisters. Even with this significant age difference, out of all my relatives, I share the strongest and deepest bond with her. The summer I was born, Gloria stayed with my mother and cared for her because of the complication of toxemia encountered during the pregnancy. Gloria was one of the first people to hold me as an infant when I came home from the hospital, and she helped care for me until my mother recovered. Studies on infant bonding have shown how an infant can experience a strong sense of unconditional love and closeness with relatives outside of their own parents. There is no denying that Gloria has a special place in my heart, and she has always been a significant part of my life, sharing laughter, joy, love, and tears. I strongly believe that in a previous life Gloria and I were bonded as sister and brother.

The use of feathers as the foundation of this assemblage is to signify the protection and preservation of an unbroken bond and transcendent love that is shared in a relationship between two first cousins. The pillow laid upon the softness of the feathers conveys the warmth of the relationship and how it provides comfort to one another.

Those close to me know I have very strong bonds with many of my sixteen first cousins. My cousins are an essential part of the family dynamic. They provide me with something I didn’t always have with my own immediate family, a sense of connection and belonging. Each of my cousins are a reminder of our family’s perseverance, will, strength and courage. They are the glue that holds our families together on an intergenerational level.

My cousin Paulette is my godmother’s daughter – our mothers were sisters. We’ve always had a close bond and been each other’s support system. We’ve witnessed every version of each other; the child, the teen, the adult, the spouse, the parent and now grandparent. Even though a few years separate us, we seem to be living parallel lives. Paulette and I always refer to one another as the male/female versions of each other. This statement is true because the two of us are interchangeable. We have very similar personalities, mannerisms and quirks. So much so, even our children enjoy calling it out and poking fun at us.

Distilling our portraits down to interchangeable pixelated color blocks, this assemblage serves as a means of intertwining our individual identities into one combined collective representation of us both.

What are the odds of three sisters born several years apart having the shared experience of being pregnant simultaneously and all giving birth to boys?

The experience of trying to get pregnant can be all consuming, filled with anxiety and mixed emotions especially when pregnancy deviates from the normal birth-order roles within your family. My mother was the last of her three older sisters and one younger sister to experience motherhood. For several years, she dreamed of being a mother but was unable to conceive. My parents decided to adopt a child and were in the final stages of adopting a baby girl, when they learned the news, my mother was pregnant with me, resulting in them never finalizing the adoption. Not only would my mother be giving birth to her first child, but she would also be sharing the experience of pregnancy simultaneously with her older and younger sister, both of whom were expecting their last child. I was born in 1962, along with my two cousins Jimmy and Michael – all within a few months of one another. We grew up together, we were raised in similar settings with similar backgrounds, shared the same milestones, core values and the three of us are close. Yet our birth order hierarchy within our respective families and role expectations within the birth order are each unique and have contributed to the shaping of our individual personalities and differences in character.

Food has always been an expression of love in my family. Typically, whenever you visited any of my relatives, the first thing out of their mouth was, “Did you eat?” Meals were magic, they created the bond that brought together and united our extended family.

Somewhat of a talisman, the handwritten family recipe holds significance. In my family, it has become one of the most cherished inheritances to be handed down through the generations. Seeing the handwritten script of a loved one is an iconic memory that immediately triggers the sensory recall to the wonderful warm memories made in the kitchen. Secret ingredients revealed, stories were told, and family traditions shared, all took place in the kitchen – truly the heart of the home.

The foundation for this assemblage is a vintage ravioli roller. The assemblage melds together three past generations of Papa women who were instrumental in sharing their love for the family meal, their homemade recipes, and a piece of their legacy to be passed down and experienced with the younger and future generations of Papa’s. While each of the Papa women stand alone in their separate squares, the overall effect of bringing them together is to represent how they each played a role in creating the Papa history and traditions our family shares today.

Tables are designed to provide support and serve as a destination point, but they can also be so much more. In most homes, the kitchen table is a timeless symbol of unity and connection. The table serves as a beacon bringing families together, fostering an environment where loved ones can gather, reconnect, and bond over a shared meal.

Growing up, Sunday was typically the designated day our family would gather at the home of my grandparents. While their kitchen table was often a place for various forms of nourishment, it also served many functions in our family. The table served as a conduit, where many of the Papa traditions and memories were born and passed down through generations. It was an art table, where my grandmother used to teach me how to draw chickens and roosters on scratch pieces of paper. At times it served as an altar, being the place where the Italian malocchio ritual was performed – a ritual consisting of oil, water and silent prayer to rid a family member of the “evil eye”. Most of my family photos are of family members gathered around my grandparent’s kitchen table in celebration of a special day or life event, making their kitchen the most photographed room in the home.

The foundation for this assemblage uses a cutting board, plate and utensil, items meant to aid in nourishment. It serves as a reminder that the kitchen table is not merely a piece of furniture, but a scared place to cherish. A place to create traditions and memories, where relationships are nourished, and bonds strengthened uniting us as families.

The early 20th-century Italian diaspora faced discrimination and negative stereotypes, with those arriving being unfairly judged based on nationality and encountering systemic hurdles in assimilating into new societies, including barriers to employment, housing, and social acceptance.

My grandfather, aged 27, emigrated from Benevento, Italy, on December 20, 1919, seeking economic opportunities and a new life. Despite his strong work ethic, he struggled with biases and derogatory labels like "Wop, Guinea, Dago, Alien, Immigrant, Foreigner, and DP," hindering his integration. A skilled craftsman and business owner, he faced obstacles from organized crime, making "monthly payments" to maintain his shoemaker shop, and being "swindled" from home ownership. Despite adversity, his survival strategy focused on hard work and family.

This assemblage serves as a narrative of the Italian diaspora and stands as a testament to the resilience of a community that, despite being bound by labels and prejudices, gradually found its place in the mosaic of global cultures.

During World War II, the Alien Registration Act of 1940 was implemented, mandating every alien aged 14 and above, including those branded “enemy aliens” from Italy, Germany, and Japan, to register at local post offices upon residing or arriving in the United States. This registration process entailed fingerprinting, photographing, and completion of a set of 15 questions designed to gather personal information and identify potential security risks, resulting in the establishment of a comprehensive database. Within a span of four months, a staggering 5 million aliens had been registered.

My grandfather had attained American citizenship, but my grandmother, who had been living in the United States for twenty years, never acquired citizenship. She was categorized as an "enemy alien", despite being the mother of eight American-born children, two of whom were serving in WWII. The process of complying with the regulations must have been incredibly daunting for her, especially considering her non-native proficiency in English. The fear of misinterpretation or answering questions incorrectly, and the possibility of being deported or imprisoned, must have been overwhelming. Assigned the alien number A2998007, my grandmother's experience reflects the anxieties and challenges faced by many during this turbulent period of history.

A2998007 incorporates a vintage fingerprint kit and ink roller, as well as the photograph and fingerprint of my grandmother that was used in her alien registration form. The assemblage consists of 850 images, each representing 6,000 individuals, symbolizing the 5 million aliens who registered within a four-month timeframe under the Alien Registration Act of 1940.

Family is comprised of complex relationships that often become entangled like threads at the bottom of a sewing kit. But when those threads are brought together like the warp and weft of a loom, they create something of substance. In that same manner, the spools represent memories of three generations of Papa consisting of my maternal grandparents, eight aunts and uncles and sixteen first cousins. My generation, consisting of first cousins, serve as the memory keepers for the Papa legacy. With that comes an obligation to preserve the values instilled, the lessons learned, the stories told, and the traditions shared with the new generation of Papa’s. Preserving the Papa history is a declaration of love for those that came before and as a legacy for remembrance to be passed down.

Photographs are prompts for recollection; they are taken in anticipation of forgetting. While this assemblage serves as the anchor piece for the series, its intent is to enhance the object’s capacity to provoke remembrance allowing for the past and the present to cohabit in the everyday.